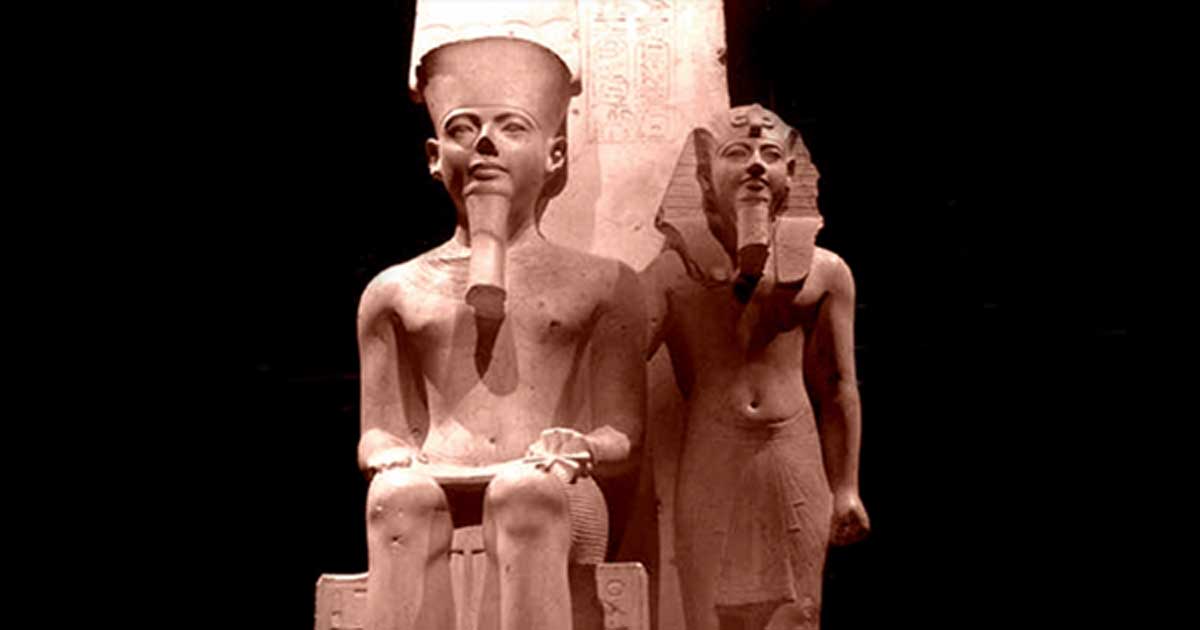

Statue of Amun and Pharaoh Horemheb

A statue depicting the god Amun seated, with Pharaoh Horemheb standing beside him.

Culture: Egyptian, Late 18th Dynasty

Date: 1319–1292 BCE

Amun is one of the most important deities of ancient Egyptian religion, especially during the New Kingdom. Originally a local god of Thebes, Amun rose in prominence and came to be identified with key aspects of creation, kingship, and hidden power. After the brief upheaval of the Atenist period under Akhenaten — in which the worship of Amun was suppressed — later rulers restored Amun to the center of state cult, rebuilding his temples and reinstating his priesthood.

Pharaoh Horemheb (reign ca. 1319–1292 BCE) was the last ruler of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty. Before ascending the throne, he served as commander of the army under Tutankhamun, and acted to restore stability after the religious and political turmoil of the Amarna period.

The relationship between Horemheb and Amun is central to his reign and legacy. Restoring Amun’s cult was both a religious and political act: it allowed Horemheb to reassert the traditional polytheistic system and reestablish the priesthood of Amun, which had been undermined during Akhenaten’s rule.

A striking work that embodies their connection is the statue of King Horemheb and the god Amun (Turin, Egyptian Museum, catalogue 768). In this statue Amun is seated on a throne, larger in scale than Horemheb, who stands beside him. The larger size of Amun emphasizes the divine hierarchy: the god’s supremacy over even the king. The statue’s style reflects the post-Amarna artistic revival — the faces are youthful, soft contours, gentler proportions, less exaggerated musculature, a return to more “classical” forms of traditional representation.

In addition, Horemheb engaged in extensive building and restoration work at the temples of Amun, especially at Karnak. He constructed, renovated, and enlarged pylons (large monumental gateways), restored damaged reliefs and statues, and used materials salvaged from previous structures (including some from the Aten period) to rebuild and reinforce Amun’s temples.

Through these acts — religious restoration, monumental art, and temple building — Horemheb sought not only to restore the cult of Amun, but also to legitimize his rule. Because Horemheb was not of direct royal descent (he was a military commander who rose to throne after the turbulence of Amarna, Tutankhamun, and Ay), anchoring his legitimacy in the traditional god Amun was a powerful strategy.