In 2015, while filming “Eye in the Sky”, Alan Rickman was already privately battling pancreatic cancer.

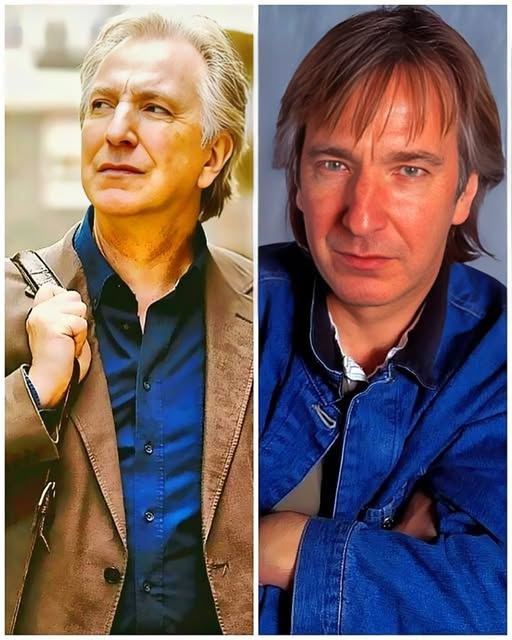

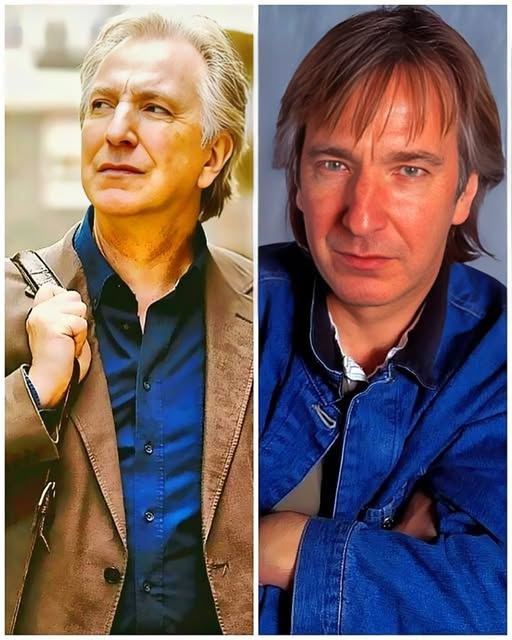

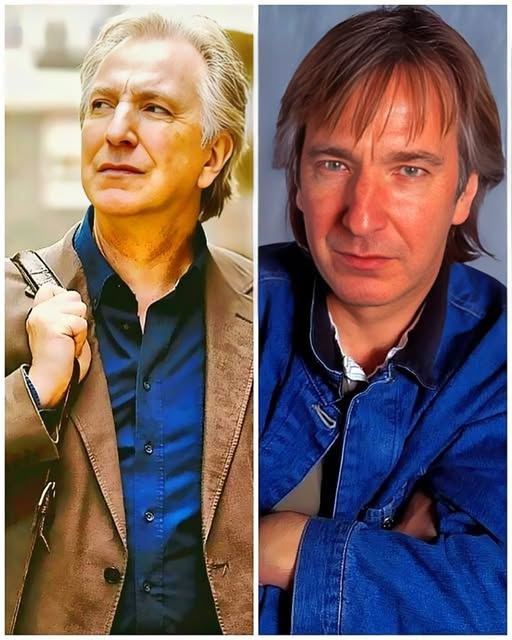

In 2015, while filming “Eye in the Sky”, Alan Rickman was already privately battling pancreatic cancer. On set, he maintained his signature poise and quiet strength, never allowing his diagnosis to cloud his work. His performance as Lieutenant General Frank Benson was sharp and layered, capturing moral tension with the same nuance that had defined his career. Very few around him knew what he was going through. Gavin Hood, the director of the film, would later reveal in interviews that Rickman had told only a handful of people about his illness. He wanted the work to speak louder than his pain.

In the months that followed, Rickman returned to voice Absolem the Caterpillar for “Alice Through the Looking Glass”, released posthumously in 2016. He recorded his lines in a London studio with technicians unaware of his condition. He moved through those sessions with a quiet focus, according to sound engineer Paul Hamblin. There was no self-pity, only professionalism and warmth.

Away from the cameras, Rickman’s days had taken a slower rhythm. He often spent quiet mornings with his wife Rima Horton, his partner of over 50 years. They had been married quietly in 2012, after decades together. He shared with friends that Rima had always been his anchor. During his final months, she was constantly by his side. The couple would often be seen walking around West London, sometimes stopping at Daunt Books or enjoying a meal at their favorite Italian spot in Notting Hill.

In December 2015, Rickman invited a few close friends for dinner. Among them were Emma Thompson and Timothy Spall. Emma later said in an interview with “The Guardian” that the evening felt like Alan’s way of saying goodbye without saying it. He didn’t talk about his illness, but there was a deep stillness to him that she hadn’t seen before. He listened more than he spoke, held eye contact a little longer, as if soaking in the moment.

One deeply personal entry in his handwritten journal from that time read, “I have always found that the line between the stage and real life is thin. Now, I feel them merging. And I am trying to hold it with grace.”

Rickman continued to engage with the world of theater and film in private ways. He wrote notes to younger actors he admired, supported causes he believed in, and stayed in touch with his Royal Academy of Dramatic Art colleagues. In a letter sent to RADA a few weeks before his death, he wrote, “Art doesn’t only reflect life—it reminds us to live it better. That’s the quiet revolution we must always believe in.”

He kept his diagnosis within a very close circle. Alan had confided in director Mike Newell during a quiet lunch in Soho. Newell later shared with “The Telegraph” that Rickman didn’t seek comfort or sympathy. He just wanted to let someone know, as a courtesy, that he may not be available in the coming months. That lunch ended with a hug and a soft “Take care of yourself,” which Newell said lingered longer than usual.

During his final days at a London hospital, Rima and his closest family members stayed close. Daniel Radcliffe visited briefly. Ralph Fiennes sent a letter. His godchildren, who referred to him lovingly as “Uncle Al,” came by one last time. The hospital staff noted how calm and dignified he remained, asking nurses about their day and joking softly when they changed his IV.

On January 14, 2016, Alan Rickman passed away in London. Hours before, Rima had held his hand and read aloud from his favorite poetry collection by T. S. Eliot. He had once told her, “I think the only way to meet the end is with curiosity. Not fear, not regret. Just a question—what now?”

His silence about the illness was not about secrecy. It was his way of keeping the spotlight on his work, not his pain. That quiet choice spoke more loudly than words ever could.