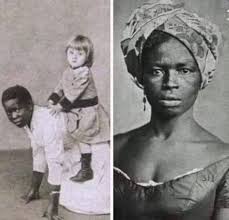

Phillis Wheatley: From Enslavement to Literary Legacy

She was named after the ship that stole her — Phillis. And Wheatley, the name of the Boston merchant who bought her. Born in Senegal, Phillis was torn from her homeland at just seven years old. On the auction block, slave traders barked, “She’ll make a good mare.” Many rough, uninvited hands touched her skin as if she were property, not a child. Naked, powerless, alone.

Yet inside her, something sacred refused to break. By the age of thirteen, Phillis was writing poetry — in a language that had been forced upon her. Her words carried rhythm, weight, and fire, but few believed they were hers. At twenty, she was summoned before a tribunal of eighteen white men in robes and powdered wigs. They demanded proof of her abilities, insisting that she recite works by Virgil, Milton, and passages from the Bible. Line after line, breath after breath, she answered every question, not to prove her worth, but to compel the world to see what was already true: she was a woman, she was Black, she was enslaved, and she was a poet.

Phillis Wheatley went on to become the first African-American to publish a book in the United States. Her pen proved sharper than any chain that had tried to bind her. Though she did not choose her name, she redefined what it meant, line by line, verse by verse, transforming it from a mark of oppression into a symbol of resilience, intellect, and enduring influence.

Phillis Wheatley’s life and work stand as a testament to the power of words and the human spirit. She took the circumstances meant to diminish her and turned them into a legacy that continues to inspire generations. Her story reminds us that even in the harshest conditions, creativity, courage, and determination can rewrite history.