The Miracle Ward: How Insulin Averted Disaster in 1922

In 1922, a team of scientists arrived at the Toronto General Hospital, where wards were filled with children suffering from advanced diabetes.

Many of the young patients were in diabetic comas, teetering on the edge of death from ketoacidosis. Others were barely surviving on starvation diets—then the only known way to slow the disease. Parents sat helplessly by their children’s bedsides, waiting for the inevitable.

Then something extraordinary happened.

The scientists went from bed to bed, injecting each child with a new purified extract called insulin. As they reached the last child, still unconscious, the very first child they had treated began to stir.

One by one, the children awoke, emerging from their comas. What had been a ward filled with grief and despair transformed into a room overflowing with relief and joy.

A Legacy of Generosity

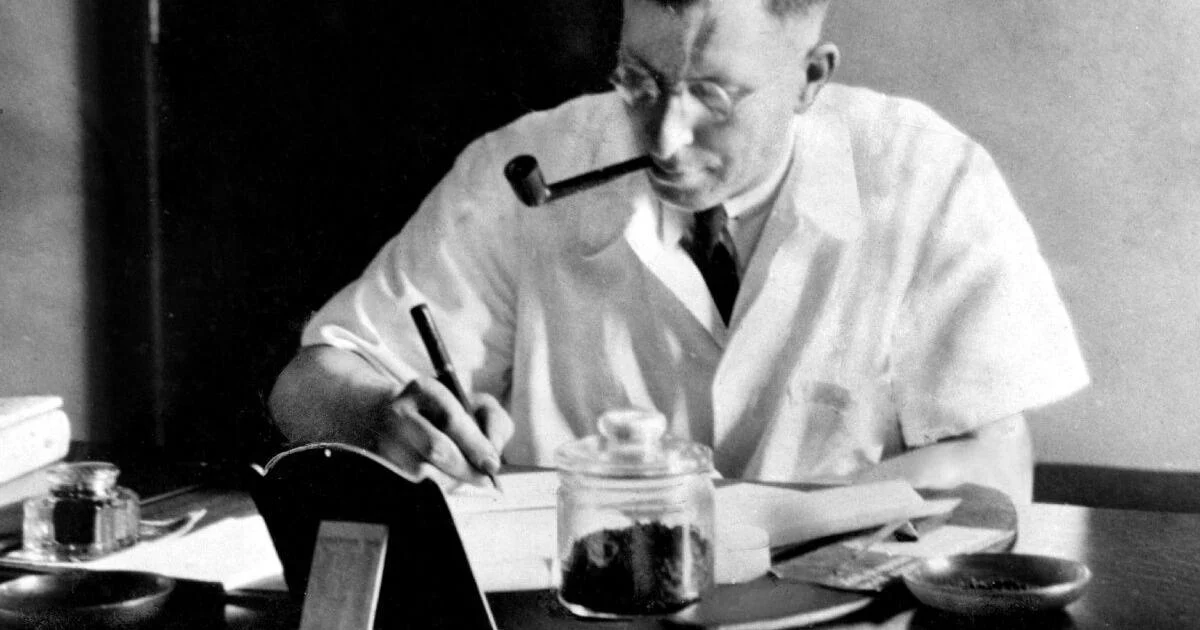

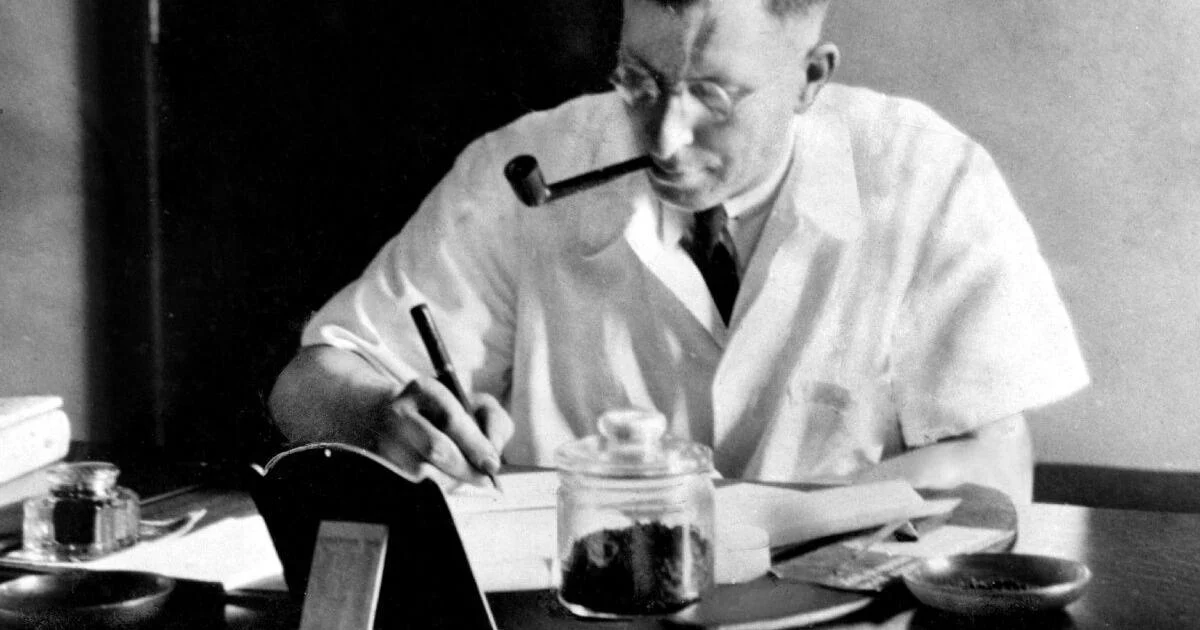

This groundbreaking moment was the result of tireless work by Frederick Banting and Charles Best, under the guidance of John Macleod at the University of Toronto. With James Collip’s help, they refined and purified insulin, making it viable for widespread medical use.

Rather than profit from their discovery, Banting, Best, and Collip sold the patent to the University of Toronto for just one dollar, believing it belonged to the world.

In 1923, Banting and Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in recognition of their life-saving breakthrough. That historic moment was not just the beginning of a new medication, but the dawn of an era of hope for millions living with diabetes worldwide.