The Ballad of ‘Ember’: A 35-Year Voyage Home

The year was 1985, and the sea off the sun-drenched coast of Jalisco, Mexico, shimmered with the heat of a scientific discovery. A small research vessel, the Triton, bobbed gently in the Pacific swell. Onboard, a young marine biologist named Dr. Elena Ramirez was training her lens on a massive humpback whale that had just executed a slow, majestic dive.

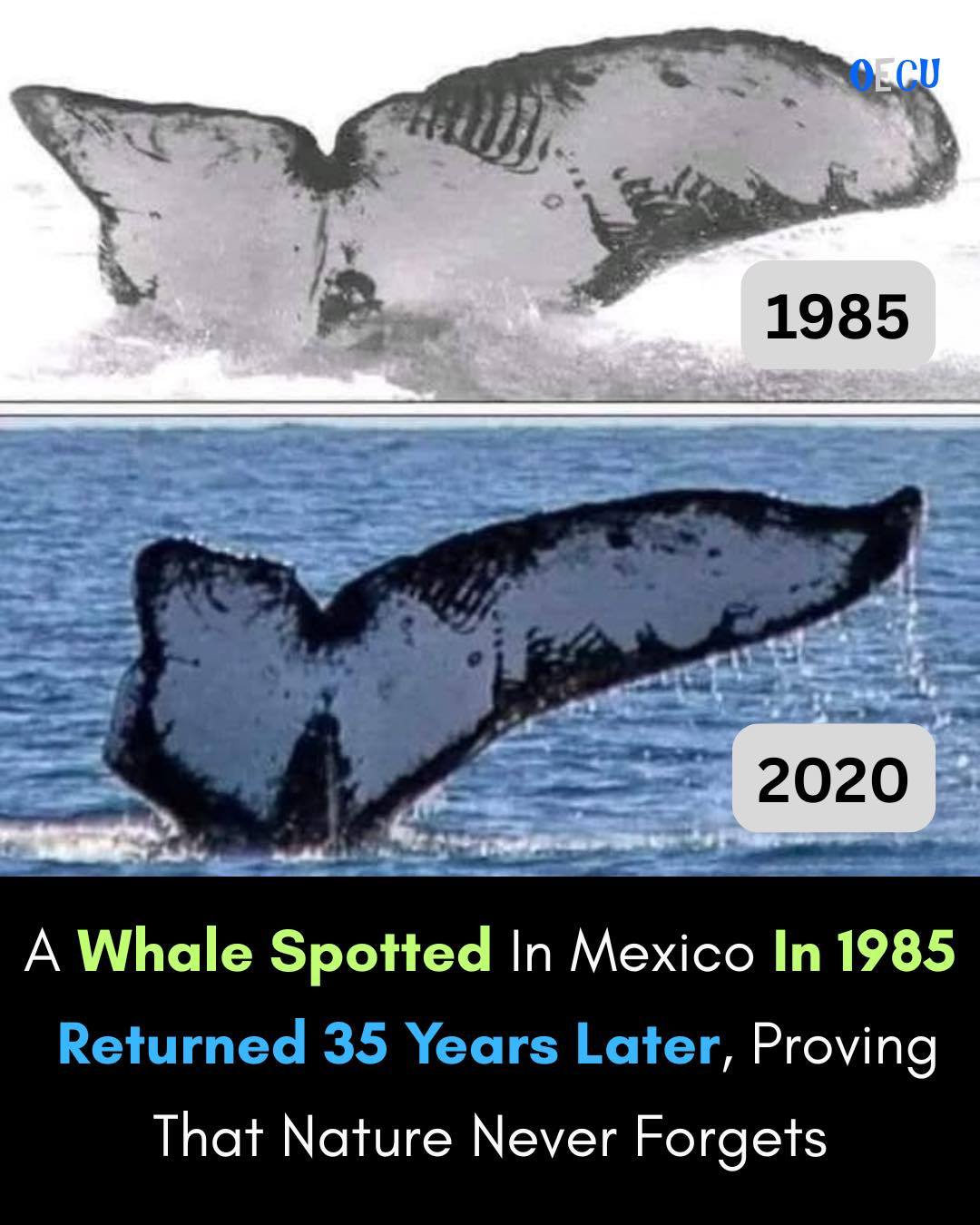

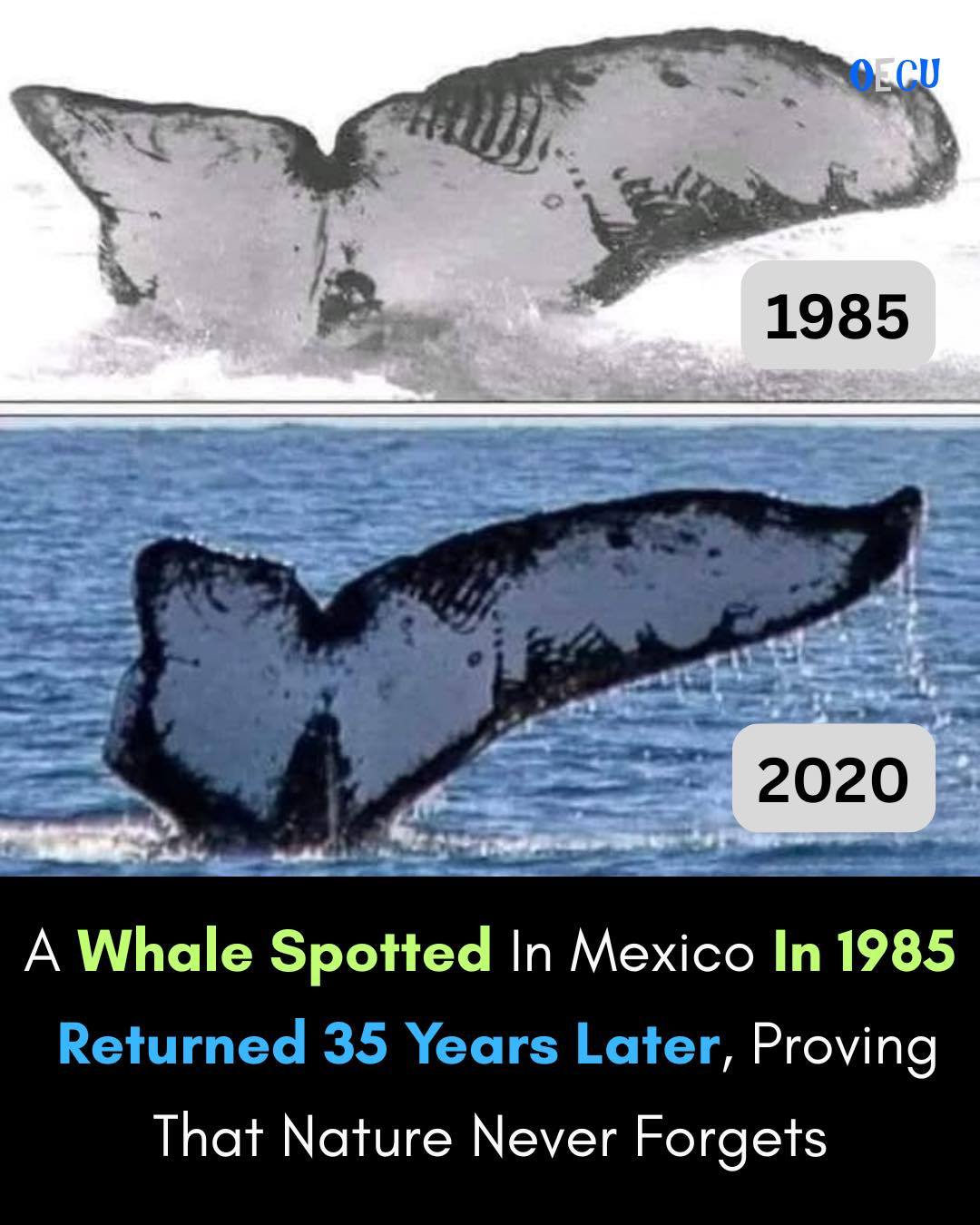

As the whale’s tail, or fluke, lifted clear of the water, the researchers snapped a series of photos. The black-and-white pattern on the underside of that fluke was unique—as distinct as a human fingerprint. They named the whale “Ember” for a faint, charcoal-like smudge near the center of the tail’s trailing edge. Ember was logged into the international photo-identification catalog, a ghost in the vast library of the ocean.

Ember, like all North Pacific humpbacks, was engaged in one of the planet’s great migrations: traveling from the warm breeding lagoons of Mexico to the nutrient-rich, frigid feeding grounds off the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia, a journey of over 5,000 miles. The question was, would she make it back?

The Silent Decades

The decades that followed brought immense change to the world above the waves—the internet exploded, borders shifted, and climate concerns grew louder. But deep beneath the surface, Ember lived her silent, immense life. She navigated by the Earth’s magnetic field, sensing the currents and the temperature shifts that guided her. She survived the nets of illicit fishing vessels and the deafening roar of supertankers, relying on the memory etched into her very being: the path home.

For 35 years, her unique pattern lay dormant in a file, a historical footnote in a dusty office. Dr. Ramirez, now a celebrated veteran in the field, had moved on to other projects, never forgetting the power of that initial photograph.

The Unthinkable Reunion (2020)

Fast forward to the summer of 2020. A team of researchers, operating hundreds of miles north in the fertile waters near the Kodiak Archipelago, Alaska, was meticulously documenting the local whale population. The weather was damp and foggy, but the krill were thick, drawing the humpbacks in droves.

On a chilly afternoon, a fluke broke the surface. The crew scrambled to capture the images, the black-and-white patterns stark against the gray water. Back on the vessel, the team uploaded the new photos to the database for matching. They were looking for individuals seen previously in the Alaskan feeding grounds.

Instead, the system returned a match that caused the lead scientist, a young woman named Maya, to gasp. The unique contours, the jagged scars, and the tell-tale charcoal smudge—it was a perfect, one-to-one match.

She cross-referenced the coordinates and the date. Ember. Identified in the Mexican breeding grounds in 1985. Now, 35 years later, Ember was in the Alaskan feeding grounds, having completed the astounding 5,000-mile journey yet again.

The Power of Memory

This was more than a cute photo match. It was a staggering validation of biological fidelity. It confirmed that, across three and a half decades and countless cycles of migration, Ember had not just returned to her migratory path, but was likely heading to the exact same feeding area she used as a young adult. The ocean had tried to swallow her, but her internal compass was unbreakable.

The story of Ember became a powerful rallying cry. It didn’t just highlight the resilience of nature; it underscored why long-term conservation and protecting both the breeding grounds in the south and the feeding grounds in the north are so vital. If one whale can show such astonishing accuracy for 35 years, traversing thousands of miles to keep an ancient promise to the ocean, then humanity owes it to her to ensure those places remain safe.

Ember’s voyage proved that the whale’s amazing journey is not a random drift, but a precise, decades-long commitment to a map carried only in the heart.