The Old View vs. The New View—How Our Understanding of Sauropods Transformed

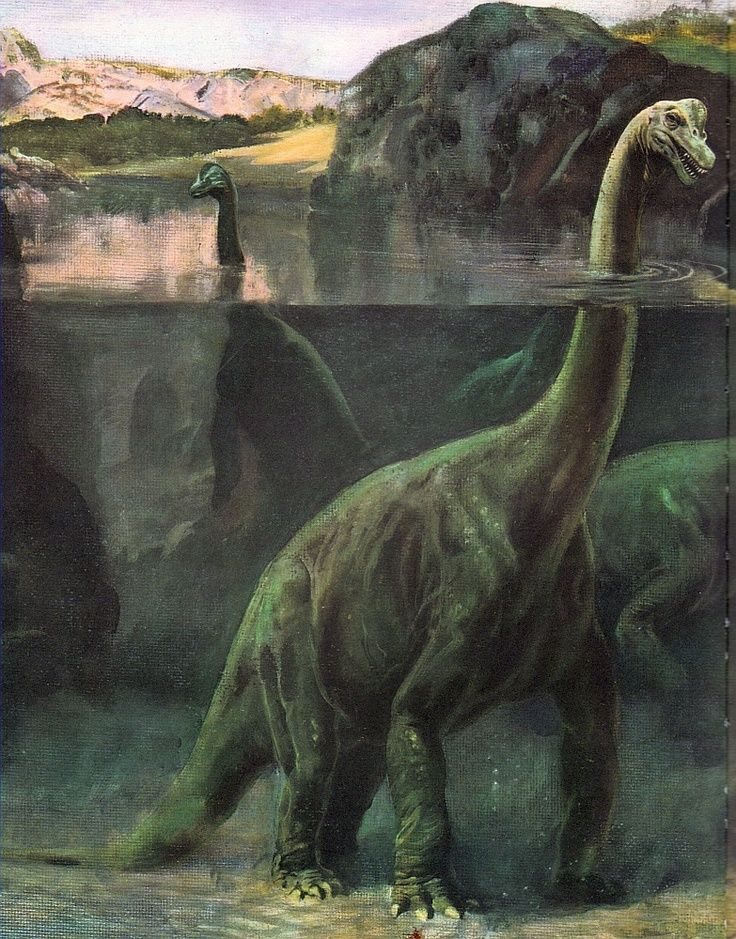

For much of the 20th century, textbooks, museum murals, and even children’s books painted a vivid image of the giant sauropods—dinosaurs like Brachiosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus—as slow-moving swamp dwellers. According to this “old view,” these behemoths were thought to be far too massive to support their own weight on land. Instead, scientists theorized they spent most of their lives submerged in lakes and rivers, using water’s buoyancy as a natural support system. Many classic paleoart depictions show herds of these long-necked giants half-hidden in murky water, their nostrils barely above the surface like reptilian submarines.

This idea wasn’t without reason. Sauropods could grow over 30 meters long and weigh upward of 50 tons, making them the largest animals to ever walk the Earth. Early paleontologists, faced with bones of such staggering size, concluded that these animals must have been semi-aquatic. They assumed the soft, marshy ground would support their weight better than dry land, and water would help relieve the strain on their massive skeletons. For decades, this interpretation dominated both science and popular culture, shaping how generations imagined the “thunder lizards.”

But modern paleontology has revolutionized this view. Advances in biomechanics, fossil analysis, and trackway studies have revealed that sauropods were not water-bound giants, but fully terrestrial creatures. Their bones tell the story: the structure of their limbs, the strength of their vertebrae, and the massive muscle attachment sites all show adaptations for carrying enormous weight on land. Their legs, column-like and straight, worked much like the pillars of a suspension bridge—perfect for bearing immense loads.

Even more compelling is the evidence from fossilized trackways. Across North America, South America, Africa, and Asia, paleontologists have found hundreds of sauropod footprints preserved in what were once floodplains and deserts. These trackways demonstrate not only that sauropods walked confidently on solid ground, but also that they moved in herds across landscapes, sometimes covering vast distances. Such evidence contradicts the old swamp theory, instead portraying them as land-based giants much like today’s elephants or giraffes—creatures perfectly adapted to dry, terrestrial life.

Modern reconstructions also highlight sauropods as active animals, capable of raising their long necks to browse from the tallest trees or sweeping them low to graze across wide fields of vegetation. Their size wasn’t a hindrance, but a highly successful evolutionary strategy, allowing them to dominate ecosystems for over 100 million years.

The shift from the “old view” to the “new view” is more than just a scientific update—it reflects the evolving nature of paleontology itself. As new tools, technology, and discoveries reshape our knowledge, our understanding of prehistoric life becomes richer and more accurate. What was once a picture of sluggish swamp-dwellers has transformed into a vision of land-roaming titans, dynamic and majestic rulers of Earth’s ancient landscapes.

In short, the sauropods didn’t need water to hold them up—they were built to carry their own colossal weight across plains, forests, and floodplains. The giants of the Jurassic were not prisoners of swamps, but true masters of the land.

#DinosaurDiscovery #SauropodScience #Paleontology