Huck and Jim in Their Final Years

Huck and Jim in Their Final Years

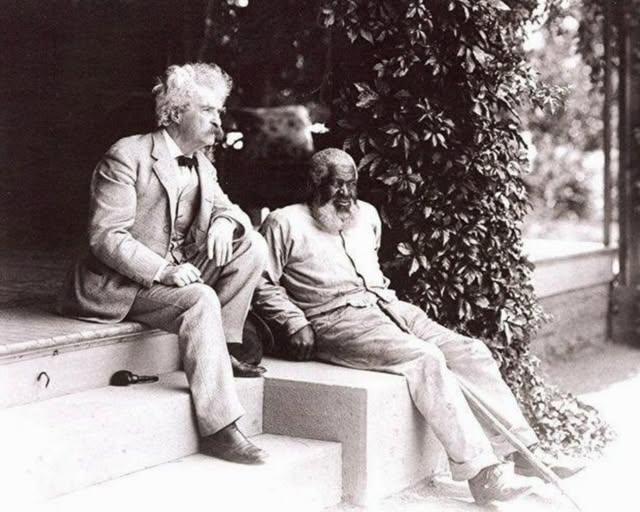

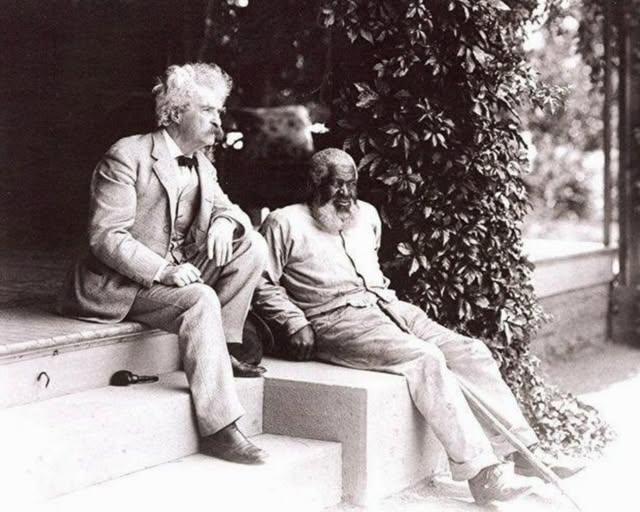

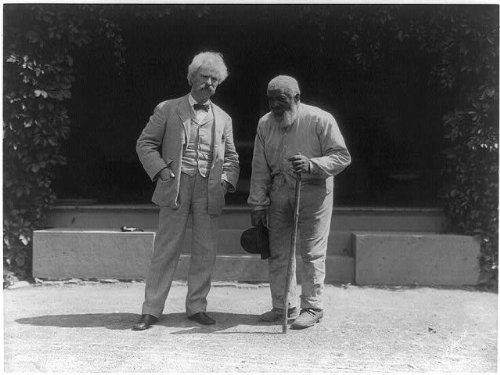

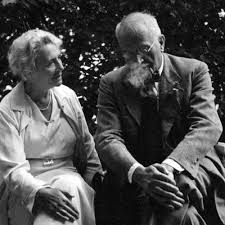

In 1903, during his last visit to Quarry Farm in Elmira, New York, Mark Twain sat for a photograph with his longtime friend, John T. Lewis. The two men, both born in 1835, had known each other for more than a quarter of a century. Their friendship was rooted not in literature or fame, but in an act of courage.

They first met in 1877 after Lewis, a free Black farmer from Maryland who had migrated north, saved the lives of Twain’s sister-in-law and her daughter. When their horse-drawn carriage bolted down a steep road, Lewis threw himself into danger, stopping the runaway team at great risk to his own life. That act of bravery earned Twain’s gratitude and began a friendship that would last until their final years.

Lewis was a man of faith, an Elder in the Church of the Brethren. He loved to read, and Twain, ever generous, sent him every book he published, each one inscribed with affection. After Lewis retired from farming, Twain and his in-laws arranged for him to receive a pension, ensuring his later years would be more secure. Their bond, built on respect and loyalty, reflected Twain’s openness to friendships that defied the racial barriers of his age.

When Twain resumed writing Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1879, he drew inspiration from Lewis. Scholars now agree that Lewis helped shape the character of Jim, Huck’s companion on the Mississippi. Some even suggest it was Twain’s acquaintance with Lewis that rekindled his determination to finish the novel after years of leaving it aside.

Twain’s friendships with African Americans were not incidental. He relished their company, valued their intellect, and rejected the hierarchies that white society insisted upon. Reflecting late in life, he recalled walking through New York City beside another Black friend, George Griffin. Passersby stared at them, puzzled at the sight of a white man and a Black man walking together. “The glances embarrassed George, but not me,” Twain said. “For the companionship was proper: in some ways he was my equal, in some others my superior.”

Published in 1884–1885, Huckleberry Finn captured the painful contradictions of race in America. Through Huck’s dawning recognition of Jim’s full humanity, Twain exposed the hypocrisy of a society that tolerated slavery. A decade later, in Pudd’nhead Wilson, he went further, dismantling the very idea of race as anything more than “a fiction of law and custom.”

As Toni Morrison once observed, “Mark Twain talked about racial ideology in the most powerful, eloquent, and instructive way I have ever read.” His friendship with John T. Lewis was more than personal—it was part of the lived experience that made his novels so enduring.

In that 1903 photograph, Twain and Lewis sit side by side, two old men in the twilight of their lives. Yet behind the quiet image lies a story of courage, loyalty, and respect—a reminder that sometimes, the greatest inspirations for literature are found not in imagination alone, but in friendship.